Stop Chasing Perfection: Design Software Around Real Problems

Blog post description.

LLD

Manu Kumar

7/1/20253 min read

In the world of software development, we're constantly told to follow principles: SOLID, clean code, design patterns, best practices. Yet, somewhere between the diagrams and the deadlines, we forget what matters most:

Solving the right problem for the business.

This post is a practical guide to rethinking design—not by following rules blindly, but by aligning our code with the problems it's meant to solve. We’ll reframe concepts like the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP), dive into Low-Level Design (LLD), and see how patterns like composition, builder, and facade truly fit into the puzzle. Spoiler: it’s not just about class diagrams.

The Single Responsibility Principle Is Not What You Think

You’ve probably heard the classic:

“A class should have only one reason to change.”

Sounds good, right? But then you wonder: what counts as a “reason”? If a class sends emails and logs metrics, are those two responsibilities—or part of the same story?

Let’s cut through the confusion.

A More Useful Definition:

A class should solve one problem at a given level of abstraction.

That’s it. No overthinking responsibilities or guessing what might change tomorrow. Just focus on solving one well-defined problem—cleanly and cohesively.

A Common Example: InvoiceService

class InvoiceService {

public Invoice calculateInvoice(Order order) { /* ... */ }

public File generatePdf(Invoice invoice) { /* ... */ }

public void sendEmail(File pdf, Customer customer) { /* ... */ }

}

Looks like a textbook SRP violation, right? Three different responsibilities—calculation, PDF generation, and emailing.

But from a business perspective, all these belong to the same process: invoicing.

So instead of reflexively breaking it up, recognize that this class is solving one unified problem. That's a win.

When Should You Actually Split Code?

Here are some time-tested heuristics:

🧩 Is it solving multiple problems?

Break it up.

👥 Do multiple teams touch this class often?

It’s likely overloaded.

🧪 Is it hard to test?

That’s a sign to extract parts.

🔄 Do its parts evolve independently?

Separate them.

🔍 Is the class name confusing?

It might be trying to do too much.

🚨 Are you seeing code duplication or fragile changes?

Decompose now.

Composition vs. Inheritance: Choose Wisely

Think of your software as a hierarchy of problems. Big problems contain smaller subproblems. Your code should mirror that hierarchy.

Use inheritance when you truly need “is-a” behavior.

Use composition when you're assembling capabilities.

Real-World Composition Example:

class InvoiceService {

private InvoiceCalculator calculator;

private PdfGenerator pdfGenerator;

private EmailService emailService;

public void handleInvoice(Order order, Customer customer) {

Invoice invoice = calculator.calculate(order);

File pdf = pdfGenerator.generate(invoice);

emailService.send(pdf, customer);

}

}

Clean. Modular. Still solving the same core problem: invoicing.

Patterns in Context: Facade, Factory, Builder

Sometimes classes look bulky—like ReportBuilder or ConnectionFactory. But remember:

They’re not breaking SRP. They’re solving higher-order problems.

Their job is to hide internal messiness and provide a simplified interface. That is a single responsibility—just a higher-level one.

So stop counting methods. Ask instead: what problem is this class solving for the user?

What Is LLD, Really?

Low-Level Design (LLD) isn’t about coding standards or diagram tools. It’s this:

LLD is the structured breakdown of business problems into solvable code units.

Before you write code, understand:

The main problem

Its subproblems

Dependencies and flows

LLD gives shape to your solution—before you open your IDE.

The Missing Piece: Domain-Driven Design (DDD)

You can’t decompose what you don’t understand.

Domain-Driven Design gives you the map. LLD is how you build the roads.

Every service, value object, or entity should tie directly to a domain concept. Without that bridge, your code becomes disconnected from reality.

Ground Design in Reality

Design isn’t about elegance. It’s about fit.

✅ Does it serve the user?

✅ Is it testable and maintainable?

✅ Does it reflect real-world concerns?

If yes, it’s a good design. Even if it violates someone's favorite rule.

A Concrete Example: PaymentGateway

Problem:

Build a payment gateway that:

Validates cards

Charges via external APIs

Logs transactions

Sends user notifications

Breakdown:

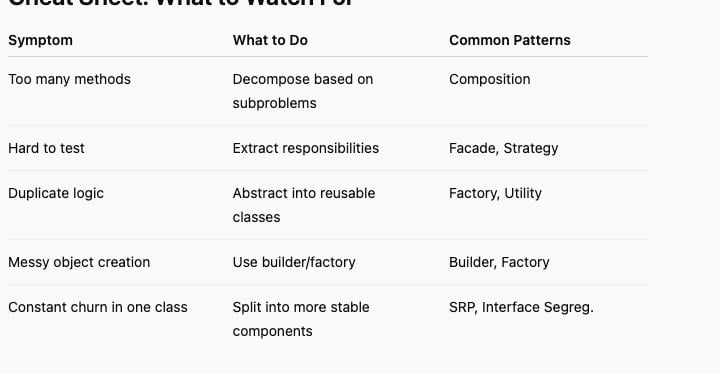

Cheat Sheet: What to Watch For

Final Takeaways

Don’t chase purity. Solve problems.

Design for clarity, not ceremony.

Business context is your compass.

Refactor when things get messy, not because a rule says so.

Good LLD always starts with understanding what the business wants to achieve.